It had a video connector, but it was up to the owner to connect a monitor. If the board was fully populated, it had 8K of dynamic RAM, allowing room to load BASIC into 4K of memory and have a little less than 4K left over for the user's programs. It was slow by today's standards, but an advancement over the teletypes that could only type 10 characters per second. (This speed would be similar to watching a computer communicate via a modem at 1200 baud). Consequently, his video terminal was somewhat slow, displaying characters at about 60 characters per second, one character per scan of the TV screen. īecause there were no cheap RAM chips available, Wozniak used shift registers to send text to the TV screen. Except for some small timing differences, he was able to use the hardware design he had earlier done on paper for the 6800. When his BASIC interpreter was finished, he turned his attention to designing the computer he could run it on. A friend over at Hewlett-Packard programmed a computer to simulate the function of the 6502, and Wozniak used it to test some of his early routines. Wozniak decided to change his choice of processor to the 6502 and began writing a version of BASIC that would run on it. MOS Technology sold their 6502 chip for $25, as opposed to the $175 Motorola 6800. However, cost was still a problem for him until he and his friend Allen Baum discovered a chip that was almost identical to the 6800, while considerably cheaper. Īnother chip, the Motorola 6800, interested Wozniak because it resembled his favorite minicomputers (such as the Data General Nova) more than the 8080. The 8080, they liked to say, had critical mass which was sufficient to consign anything else to oblivion. The sheer weight of the programs and the choice of peripherals, so the argument went, would make it more useful to more users and more profitable for more companies. The people who wrote programs or built peripherals for 8080 computers thought that later, competing microprocessors were doomed. Disciples of the 8080 formed religious attachments to the 8080 and S-100 even though they readily admitted that the latter was poorly designed. The junction of these peripheral devices for the Altair was known as the S-100 bus because it used one hundred signal lines.

The private peculiarities of microprocessors meant that a program or device designed for one would not work on another.

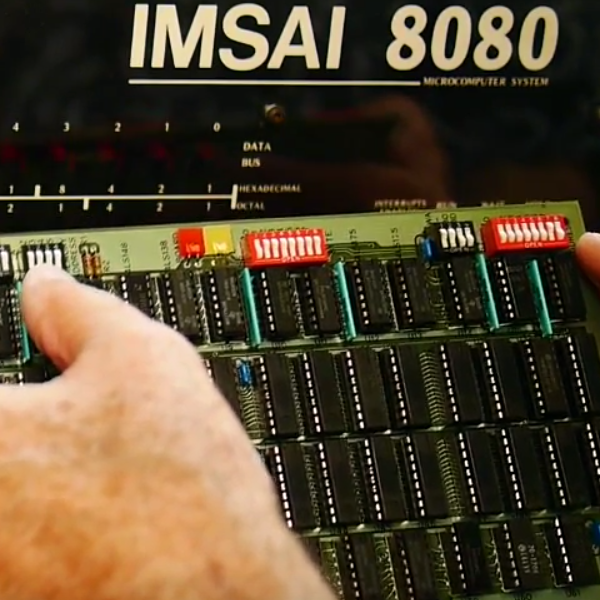

The Altair was built around the 8080 and its early popularity spawned a cottage industry of small companies that either made machines that would run programs written for the Altair or made attachments that would plug into the computer. That summer at the Homebrew Club the Intel 8080 formed the center of the universe.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)